One in four UK mammals are threatened with extinction.

The British Isles and Ireland are home to many species of mammal, from the common shrew to grey seal. We work toward a future where populations thrive as part of healthy and diverse ecosystems benefiting people and nature.

Current research View all

Discover British mammal species

With approximately 90 species spanning across land, air, and sea, there are many fascinating creatures to learn about. From iconic land-dwellers like red foxes and badgers to majestic marine mammals like seals and dolphins, the British Isles are home to a rich tapestry of mammals.

News and stories View all

Learn with our on-demand learning library

Missed one of our live webinars? Access expert-led sessions anytime, anywhere.

Join the Local Groups Network

A growing movement of mammal enthusiasts across Britain.

From the world of mammal conservation

Stay informed about the latest mammal news, tips and events in our newsletter.

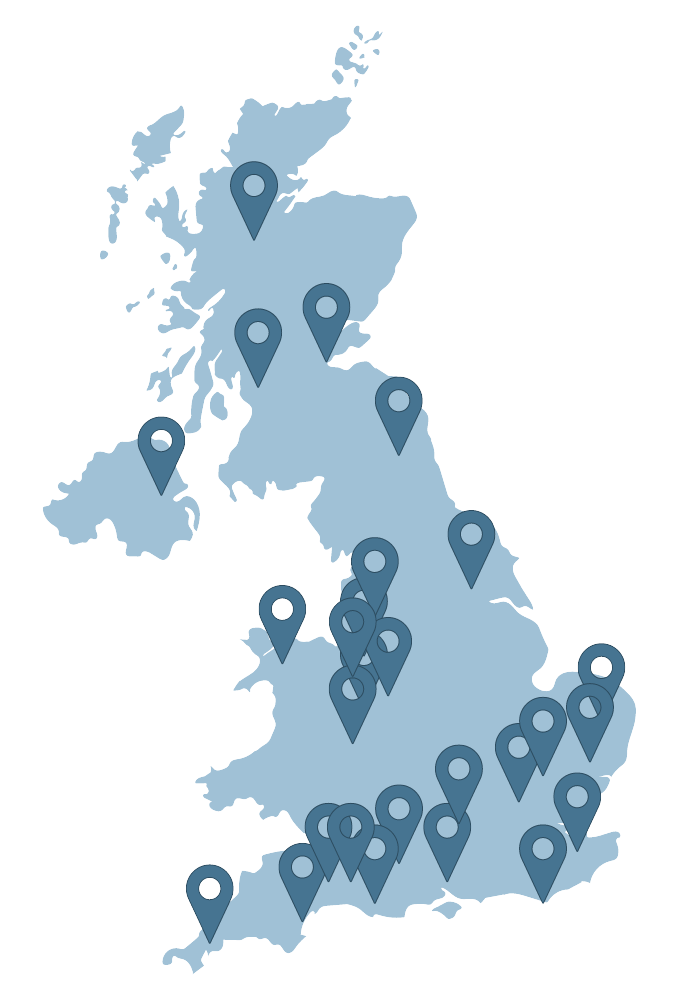

Discover the Local Groups Network

Our local groups support a growing movement of mammal enthusiasts across the British Isles and Ireland. Discover a group near you and join alongside like-minded individuals who are dedicated to safeguarding mammals.

From the world of mammal conservation

Stay informed about the latest mammal news, tips and events in our newsletter.

Take part in National Mammal Week 2024

Find out how you can get involved in National Mammal Week this 2024.

Join your local mammal group

A growing movement of mammal enthusiasts across Britain.